27/02/17

Women and books are not every man’s best friends

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Sister Joan Agnes of the

Cross. The Tenth Muse. The illegitimate child. The self-taught scholar. She was born in San Miguel Nepantla, near Mexico City, which was part of the Spanish Empire, in 1651. Having learned how to read and write at age 3, she devoured every book she found in her grandfather’s library. Books both appropriate and forbidden, according to the wisdom of a Church composed of fallible men. By virtue of her brilliant mind, she harvested admiration and envy. And the strength of the latter, naturally, resonated across her body, her spirit, her legacy. Much has been said, much has been hidden. A fascinating and controversial figure brimming with beauty and the rare charms of wit. I was instantly captivated by her life and poetry, which echoes the lyrical nature of a restless soul. Her verses disclose the desire for knowledge, the delights of a good argument, the sensuous beauty of the flesh, the chants to the divine, the impulse of a free spirit and a constrained body. Truths essentially secular, revelations intrinsically sacred. Breathtaking complexity. Confusion and longing.

The unbearable heaviness of being.

Este amoroso tormentoEste amoroso tormentoque en mi corazón se ve,sé que lo siento, y no séla causa por qué lo siento.Siento una grave agoníapor lograr un devaneoque empieza como deseoy para en melancolía.…Siento mal del mismo biencon receloso temor,y me obliga el mismo amortal vez a mostrar desdén.*This amorous tormentThis amorous tormentwhich in my heart can be seenI know I feel it yet don’t knowthe reason of this feeling.I feel a strong agonyat having a dalliance,that begins as desireand ends in melancholy....I feel bad for good itselfwith suspicious fearand obliged by the same loveperhaps to show disdain.

The young Juana Inés couldn’t even touch the threshold of the university, not even while wearing men’s clothes, as she once naively contrived, so she decided to wear a religious habit in order to assuage her thirst for knowledge. An activity which wouldn’t interfere with her studies, and probably would save her from her condition of illegitimacy, as stated by some sources. A bold decision that not always lived up to her expectations, for being married to God meant prayers and penitence, cooking, needlework, cleaning, more penitence. Her spiritual marriage didn’t involve reading and writing about worldly matters. It didn’t involve philosophy, theology, logic nor passion. It didn’t involve thinking. Nonetheless, Juana Inés, now Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, had other plans which obeyed the talents that God, her creator, for some reason gave her.

Insinúa su aversión a los vicios¿En perseguirme, mundo, qué interesas?¿En qué te ofendo, cuando sólo intentoponer bellezas en mi entendimientoy no mi entendimiento en las bellezas?*Suggesting her aversion to viceO World, why do you wish to persecute me?How do I offend you, when I intendonly to fix beauty in my intellect,and never my intellect fix on beauty?

After some years, and particularly since 1690 (the year when she dared to question the theological views of one celebrated Portuguese Jesuit preacher), a nun and her wondrous quill became an ecclesiastic insult. An inexcusable transgression. An unpardonable song of rebellion in a world where some women truly believed the small fate imposed by men, while others nodded in despairing acquiescence.

Finjamos que soy felizFinjamos que soy feliz,triste pensamiento, un rato;quizá prodréis persuadirme,aunque yo sé lo contrario...…Si es mío mi entendimiento,¿por qué siempre he de encontrarlotan torpe para el alivio,tan agudo para el daño?*Let us pretend that I'm happyLet us pretend that I'm happy,sad thought, for a while;you may actually persuade mebut I know otherwise...If it's mine my understanding,Why always must it beSo dull and slow to pleasure,So keen for injury?

After watching a biopic, a series on Netflix, and reading a brief biography, I thought it was time to get acquainted with this brilliant woman's work (otherwise, I confess, I wouldn't have paid her much attention). A person who defended women's right to gain knowledge like any other man, in a time when a woman was considered an inferior being and the source of all sin; a time when reading Copernicus was the safest path to the diverse punishments inflicted by the Inquisition.

It was an interesting social experiment to compare a protest I witnessed a couple of weeks ago, where women decided to protect her rights by going topless (watch out, Wollstonecraft) with a woman who, amid the ignorance and misogyny of a harsh 17th century, decided to defend those same rights with her mind. A religious woman whose quill didn’t shiver and once wrote to

foolish men, who accuse/Women without good reason/You are the cause of what you blame/Yours the guilt you deny...

By 1693, Sor Juana Inés relegated her literary creativity. She, the worst of all women, was forced to repent by the pressure of the Church, embodied by Francisco de Aguiar y Seijas, Archbishop of Mexico, for being a vain spirit too attached to earthly matters, for neglecting her duties as a nun, for daring to think like a man. Her books, her musical instruments, her scientific tools – everything was sold or confiscated, depending on the source. Her intellectual force couldn’t resist the clerical opposition which not only would affect her, but her Sisters as well. In that context, her words were no longer published; she immersed herself in the activities of the convent. She died in 1695 during a plague, while taking care of other stricken nuns.

According to some documents, after Sor Juana Inés' death, several writings – sacred and profane – were found in her room. She never published a word in the eyes of the Church again, but she never stopped writing either.

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. The heavens and the earth tried to conquer her beautiful mind.

Dime vencedor rapaz…En dos partes divididatengo el alma en confusión:una, esclava a la pasión,y otra, a la razón medida.Guerra civil, encendida,aflige el pecho importuna:quiere vencer cada una,y entre fortunas tan varias,morirán ambas contrariaspero vencerá ninguna.…pues podré decir, al vermeexpirar sin entregarme,que conseguiste matarmemas no pudiste vencerme.*Ascendent raptor speak…My soul is cleftconfusedly in twain.Half - a thrall to passion,the other - reason's slave.Civil war, inflamed, importunateafflicts this breast:each strives to overwhelm his counterpart;but amidst such mutinous counterstorms,both helmsmen must perish,neither, return to port.…since it will be said - to see me fallyet not surrender -that you managed to killbut failed to conquer.

The mind that saw no obstacle in gender or time. That put common citizens, sensible clergymen and viceroys under her intellectual spell. That gained her inveterate enemies but also kind-hearted friends who remained admiring her work during the worst of times, and after her death. That transcended the limits of her body. For being enamored with the mind of another human being is the most long-lasting connection to which anyone may aspire.

* 4.5 stars. I wasn’t exactly thrilled by this edition. I noticed that there were one or two incomplete versions of poems and no indication - vexing. If you know Spanish, you may want to look for another collection.

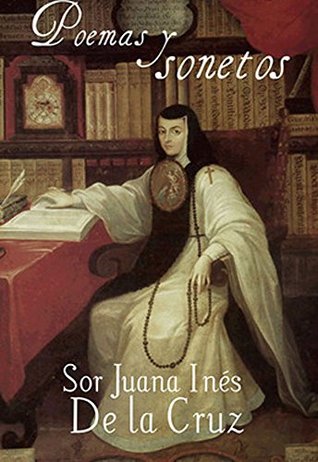

* Photo credit: Book cover via Goodreads.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario